Ocker Gevaerts and the First Bank of the United States

The First Bank of the United States aimed to address issues like war debt and inflation, as well as standardizing currencies within the country. Though successful, the Bank met with resistance from Founding Fathers like Thomas Jefferson.

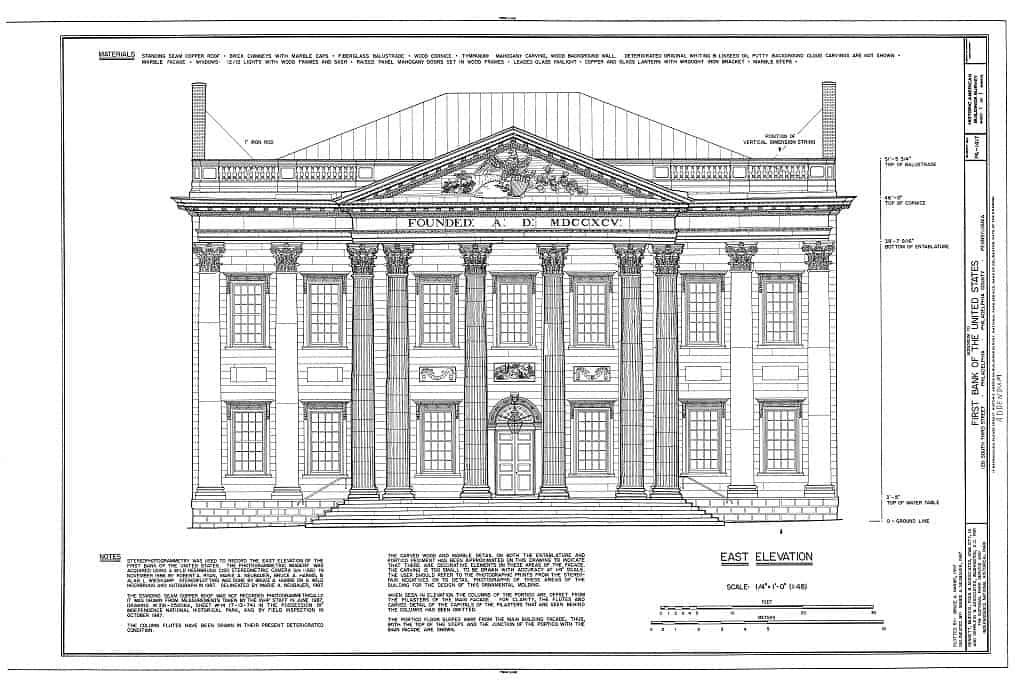

Header Image: Plans containing the details for the First Bank of the United States. [1].

“The tendency of a national bank is to increase public and private credit. The former gives power to the state, for the protection of its rights and interests: and the latter facilitates and extends the operations of commerce among individuals…and herein consists the true wealth and prosperity of a state.”

Alexander Hamilton, who helped to establish the Bank of the United States; courtesy Library of Congress

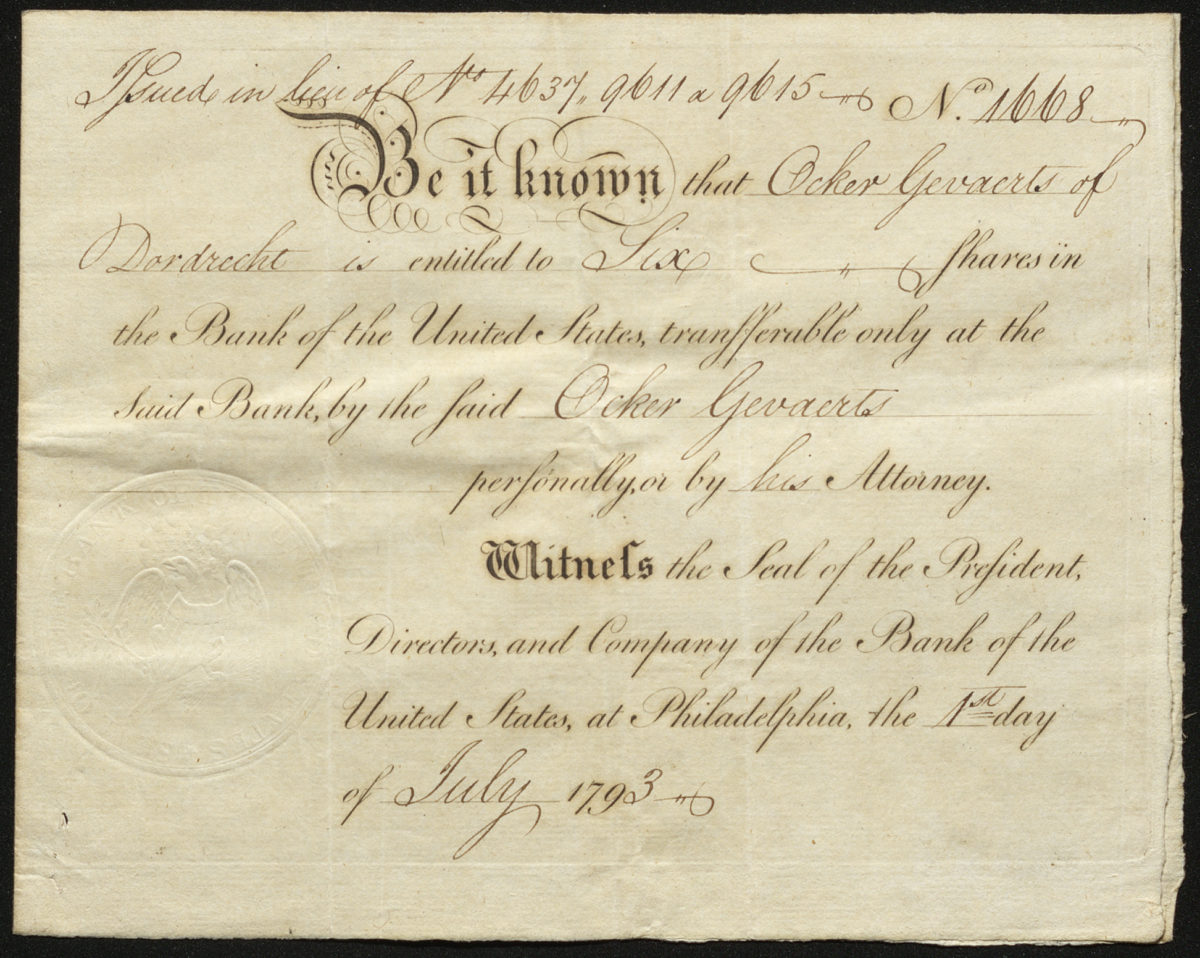

This certificate is for stock in the First Bank of the United States—referenced here simply as the Bank of the United States—from 1793. Alexander Hamilton proposed the Bank of the United States as a solution to the fledgling country’s economic woes. The United States had accumulated millions of dollars’ worth of debt during the American Revolutionary War. Inflation was high, and banks in each state had been producing their own currencies, adding to the chaos. The Bank of the United States was established under President George Washington with aims to reduce war debt, lower inflation, and create a standardized currency.

The Bank was established in 1791 and financed by $10 million in stock. One-fifth of this was held by the government, and the other eighty percent was sold off for $400 a share to private investors. One of these private investors was Ocker Gevaerts of Dordrecht, the Netherlands, whose name appears on this document. Gevaerts was a Dutch capitalist who was serving as the Mayor of Dordrecht the at the time he owned this stock.

The Bank of the United States was well-managed and profitable, but when the charter that created the bank came up for renewal in 1811, it met opposition. Thomas Jefferson had opposed the initial creation of the Bank, believing that it was unconstitutional and undermined state banks. Many others agreed with this assessment, and believed the Bank violated states’ rights.

The charter was not renewed, and the First Bank closed operations in 1811. The following year the War of 1812 brought a return of the same problems that had existed before the First Bank: war debt, inflation, and the over-issuance of different currencies from state banks. The Second Bank of the United States was established shortly thereafter, in 1916, though this bank was mismanaged. The Second Bank met the same fate as the first, closing its doors in 1836.

The building that the First Bank occupied still stands in downtown Philadelphia. It was built in the 1790s, while the city was temporarily serving as the nation’s capital. It has been purchased by the National Park Service and was restored for our nation’s Bicentennial in 1976. The portico features a bald eagle with a United States shield, arrows, olive branch, and cornucopia—an image similar to the seal embossed at the bottom right of this document. The eagle grasps an olive branch representing peace, arrows representing war, and is crowned by a cluster of thirteen stars representing the original thirteen colonies. On the portico, the additional cornucopia represented bountiful harvest and in this context, prosperity.

University of Nevada, Reno

University of Nevada, Reno