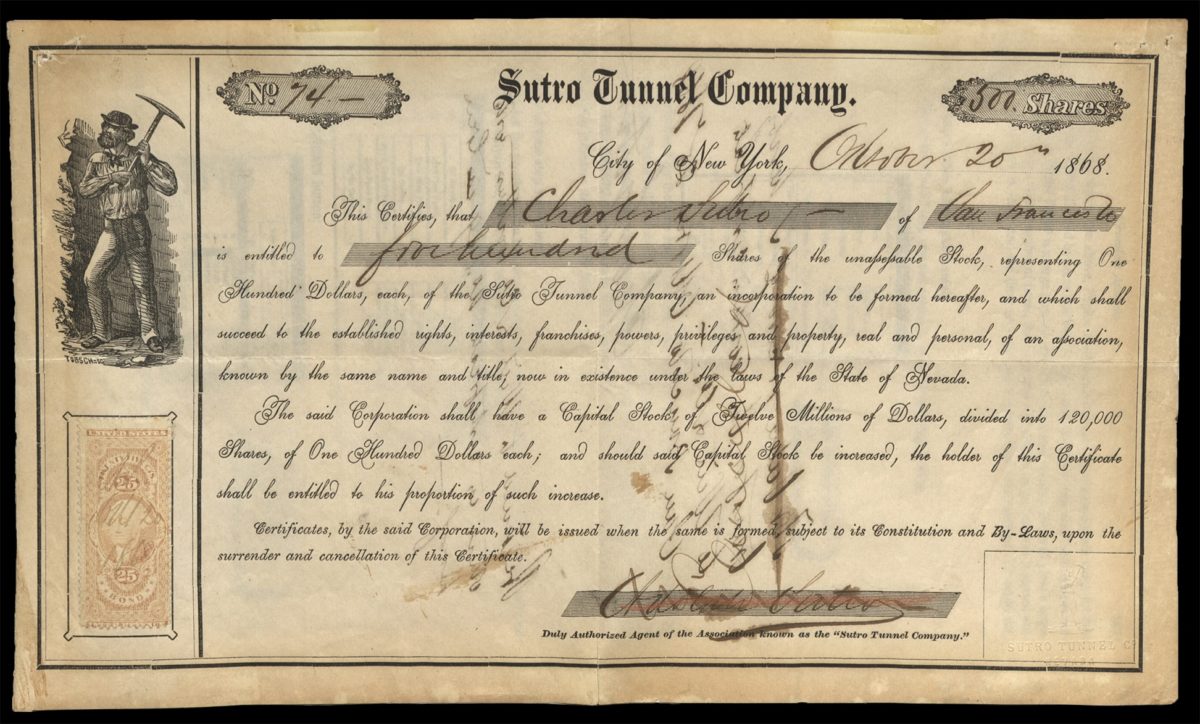

The Sutro Tunnel: Capitalism at Its Finest

The struggle over the construction of the Sutro Tunnel represented a struggle for power in Virginia City. The Comstock’s Bank Crowd tried to prevent the Sutro Tunnel from attracting investments, as they believed it would undermine their monopoly in the region.

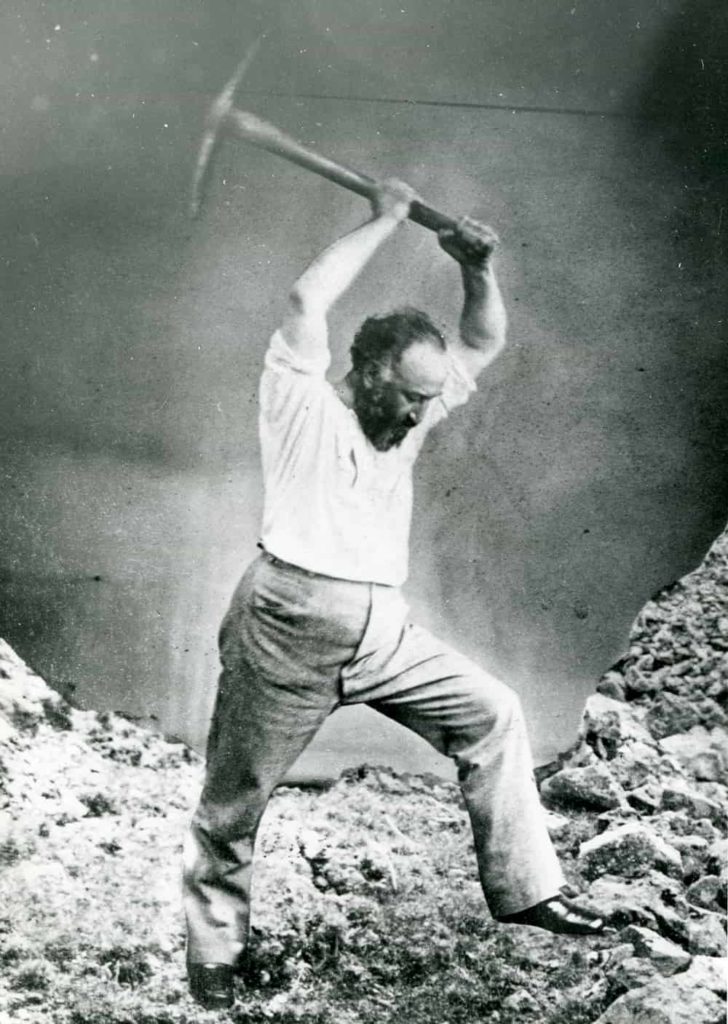

Header Image: Adolph Sutro poses raising a pick axe; courtesy Special Collections Department, University of Nevada, Reno Libraries. [1].

“[The Sutro Tunnel was] a bold fraud from beginning to end”

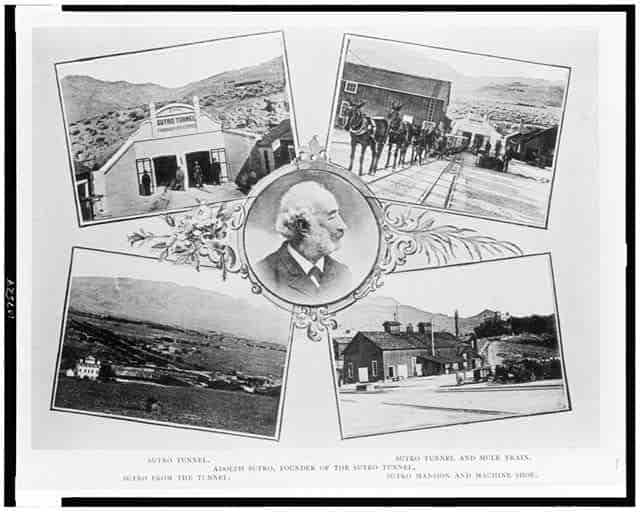

Adolph Sutro, the tunnel, and images of the town of Sutro; courtesy Library of Congress

Adolph Sutro, a San Francisco entrepreneur, conceived the idea for the Sutro Tunnel when he visited the Comstock Lode in 1860. He believed it was a practical solution to several of the costs and problems of deep mining in the Comstock, such as the drainage of water, ventilation, and easier removal of ore. His plan was to build a horizontal tunnel from the base of the hills near Dayton, tunneling nearly four miles to intersect with the mines of the Comstock. The Sutro Tunnel Company would profit by charging the mines $2 per ton of ore extracted. Sutro would also make money from real estate as owner of the land surrounding the tunnel entrance and from the milling operations he built.

Though Sutro received government backing for the tunnel, William Sharon’s Bank Crowd opposed and undermined it, preventing construction for years. The Bank Crowd monopolized mining operations in Virginia City in the 1860s and saw the Tunnel as a threat to their Virginia & Truckee Railroad. Sutro advertised to investors that his project and the town of Sutro would replace Virginia City as the center of Comstock operations. As author Alexander H. Waterman expressed, “Sutro had stated publicly that eventually he and his tunnel would dominate the Lode with all mining being done through the tunnel, reducing Virginia city to the status of a ghost town.”

The Bank Crowd, with pull in the financial world, prevented the tunnel from receiving investments and attempted to have government backing of the project revoked. After years of fighting, the disaster at the Yellow Jacket Mine finally tipped the scales in Sutro’s favor. After thirty-five men were killed in an underground mine fire in 1869, Sutro met with the miners’ unions to discuss the safety benefits of his tunnel: it would provide an alternate escape in the event of an emergency, and the ventilation it provided could have prevented numerous deaths due to suffocation. The miners gave him $50,000, and work on the Sutro Tunnel began in October of that year. (Scroll down to continue reading about the Sutro Tunnel below)

It took almost a decade to complete the tunnel, which spanned 20,489 feet from the town of Sutro to the Comstock, and cost over $2 million. By the time workers reached Virginia City’s mines in 1878, the mining district was on the cusp of collapse as mine after mine closed operations. Adolph Sutro had the foresight to sell his stock in the Sutro Tunnel Company when prices were around $6.50 a share, before they crashed to 6¢. He made a fortune off the project even though the tunnel was never profitable. Some accused him of being fraudulent and even referenced his Jewish heritage by calling him a shylock.

Adolph Sutro retired with his wealth to San Francisco and invested in real estate. It is estimated that at one point he owned one-twelfth of the land in San Francisco, and he invested in projects like the Sutro Baths and Sutro Heights. He served as Mayor of San Francisco 1895–1897.

University of Nevada, Reno

University of Nevada, Reno