George Graham Rice: The Jackal of Wall Street

Con artist George Graham Rice loudly proclaimed his own innocence and blamed people like George Wingfield for stock manipulation schemes, but Rice’s record of imprisonments speaks to his integrity.

Header Image: The L.M. Sullivan Trust Company office in Goldfield, Nevada, which is believed to have served as a front for George Graham Rice’s stock manipulation schemes; author Larsen Photo courtesy Special Collections Department, University of Nevada, Reno Libraries [1].

“Rice… needs no introduction to the citizens of Nevada, as he operated here for some years following the Goldfield boom, and wherever he has lived in recent times he has been in the limelight”

Rice beckons investors, “Follow me into oil” in the Ogden Examiner, 1918; courtesy Newspaper Archive

Mr. Wingfield was about thirty years old. Of stinted, meager frame, his was the extreme pallor that denoted ill health, years of hardship, or vicious habits. His eyes were watery, his look vacillating. Uncouth, cold of manner, and taciturn of disposition, he was the last man whom an observer would readily imagine to be the possessor of abilities of a superior order. In and around camp he was noted for secretiveness. He was rated a cool, calculating, selfish, surething gambler-man-of-affairs—the kind who uses back stairs, never trusts anybody, is willing to wait a long time to accomplish a set purpose, keeps his mouth closed, and does not allow trifling scruples to stand in the way of final encompassment.

–George Graham Rice, My Adventures With Your Money

The “Jackal of Wall Street” George Graham Rice, who painted this unflattering portrait of George Wingfield, had a persuasive way with words. This skill served him well as a con man promoting mining stock frauds in the early 1900s. Born Jacob Herzig in New York in 1870, he changed his name to George Graham Rice to distance himself from his early convictions for stealing from his father’s company. Rice moved to Goldfield, Nevada in 1904 where he operated the L.M. Sullivan Trust Company, a stock manipulation scheme. Rice, along with the L.M. Sullivan Trust Company, sponsored a boxing match between Joe Gans and Oscar “Battling” Nelson in 1906. The fight was another of Rice’s publicity ploys—similar to his actions in Rawhide—drawing media attention to Goldfield and its mining stocks. The fight was thrown in favor of Gans, the fighter Rice had bet on.

Rice moved to Reno after the L.M. Sullivan Trust Company failed in 1907, which along with the national market Panic of 1907, precipitated the collapse of values of all stocks from Goldfield. Rice publicly blamed L.M. Sullivan’s failure on the local bankers and Goldfield Consolidated Mining Company owners George Wingfield and Senator George Nixon. Rice accused them of manipulating politics, the banks, miners, and the press to their own benefit and further claimed that Wingfield and Nixon engineered the financial collapse of Goldfield so they could take over the town’s other banks and desirable properties. (Scroll down to continue reading about George Graham Rice below)

In reality, the L.M. Sullivan Trust Company was one of several ill-fated ventures in which Rice was involved. The next was B.H. Scheftels & Company of New York, a business known as a “bucket shop” which offered inexpensive commissions to lure in investors but used funds to gamble on the market instead of actually purchasing stocks. The office was raided by U.S. Postal Agents in 1910, as Rice and his associates had been using the mail service to send fraudulent information about stocks.

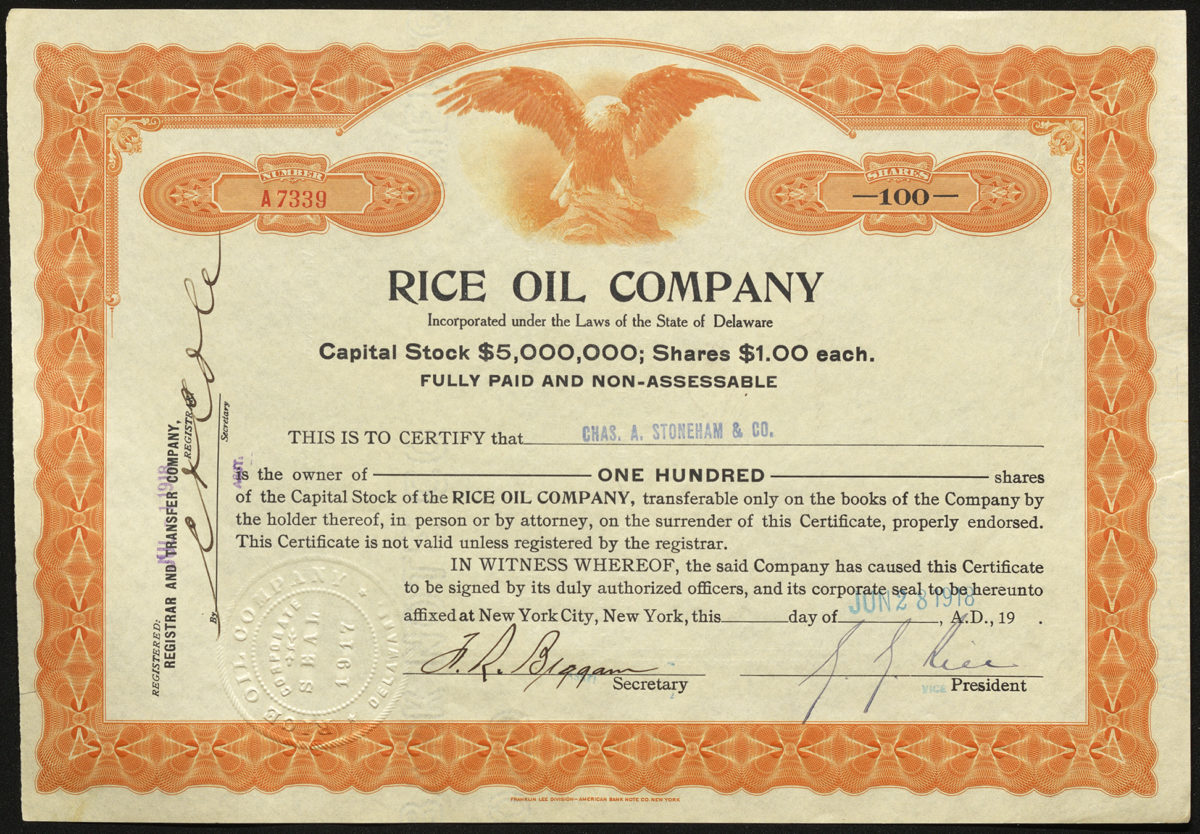

Rice was arrested, pleading guilty to mail fraud, though he claimed innocence in the matter. He wrote the book My Adventures With Your Money while he was imprisoned for a year and used the platform to lay blame at the feet of a vindictive George Wingfield, while also claiming a larger conspiracy between bucket shops and government agents. Rice famously maintained a “sucker list” with the names of over 65,000 customers. Part of this list had been stolen by a detective during the 1910 raid on his office and was supposedly sold to rival bucket shop operator Charles A. Stoneham—whose company stamp appears on this stock certificate. Rice later testified that Stoneham had bribed Post Office Inspectors $2,500 to target B.H. Scheftels & Company.

This certificate for the Rice Oil Company of Kentucky is from 1918. Apparently having learned his lesson, Rice changed his tactics by advertising the company as the “greatest speculative opportunity of recent years” in newspapers in 1916-1917 and added more names to his sucker list by soliciting people to write for more information. Shortly after this stock certificate was signed, Rice was again arrested for fraudulent stock dealings and convicted of grand larceny. In the Supreme Court of Appeals proceedings, Rice again concocted an elaborate story to shift the blame away from himself. He claimed that a group of bucket shoppers—among whom Stoneham was named first—were being protected by crooked government agents and had conspired to frame Rice.

Rice testified that Stoneham “has been the best protected bucket shop in America, beyond the pale of any interference, and now he has got money and bought the baseball club with it.” In this last statement, Rice was referring to Stoneham’s purchase of the New York Giants baseball team in 1919 for $1 million, a deal brokered by the mobster Arnold Rothstein responsible for fixing the 1919 World Series.

University of Nevada, Reno

University of Nevada, Reno