Nevada Revolves Around Tonopah & Wingfield

In its heyday, the mines of Tonopah and Goldfield fueled a resurgence of wealth and power after the ending of the Comstock Lode. From this emerged a new class of prominent Nevadans including George Wingfield, Patrick McCarran, and Tasker Oddie.

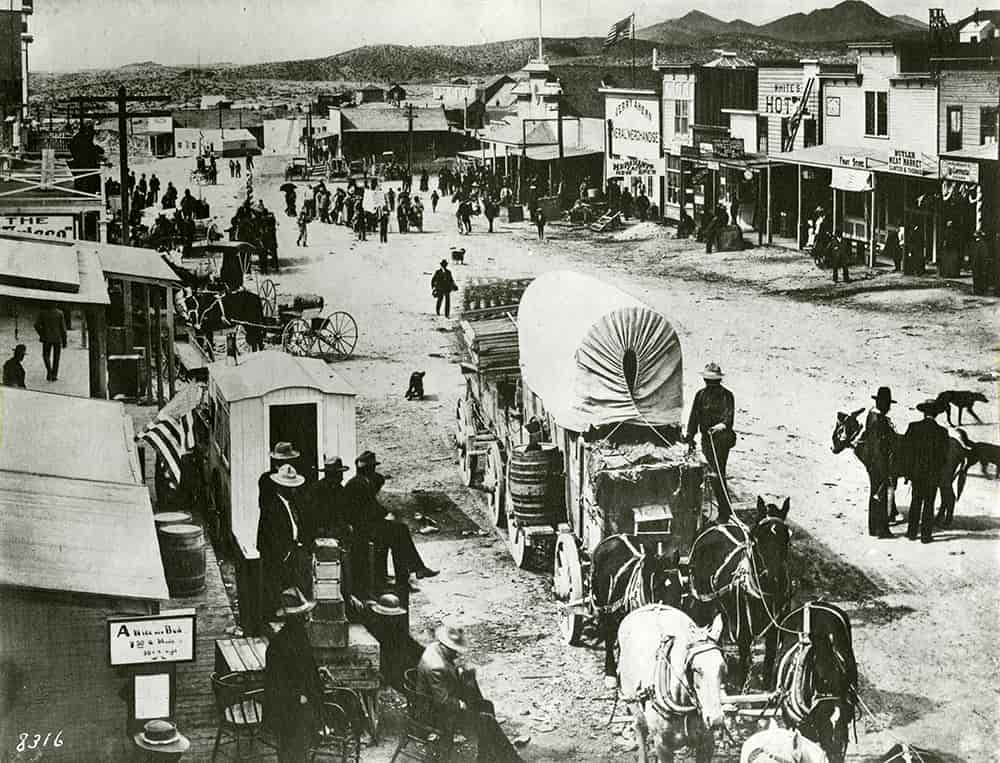

Header Image: The fledgling town of Tonopah in 1903; courtesy Special Collections Department, University of Nevada, Reno Libraries [1].

“George Wingfield is strictly a product of the West.”

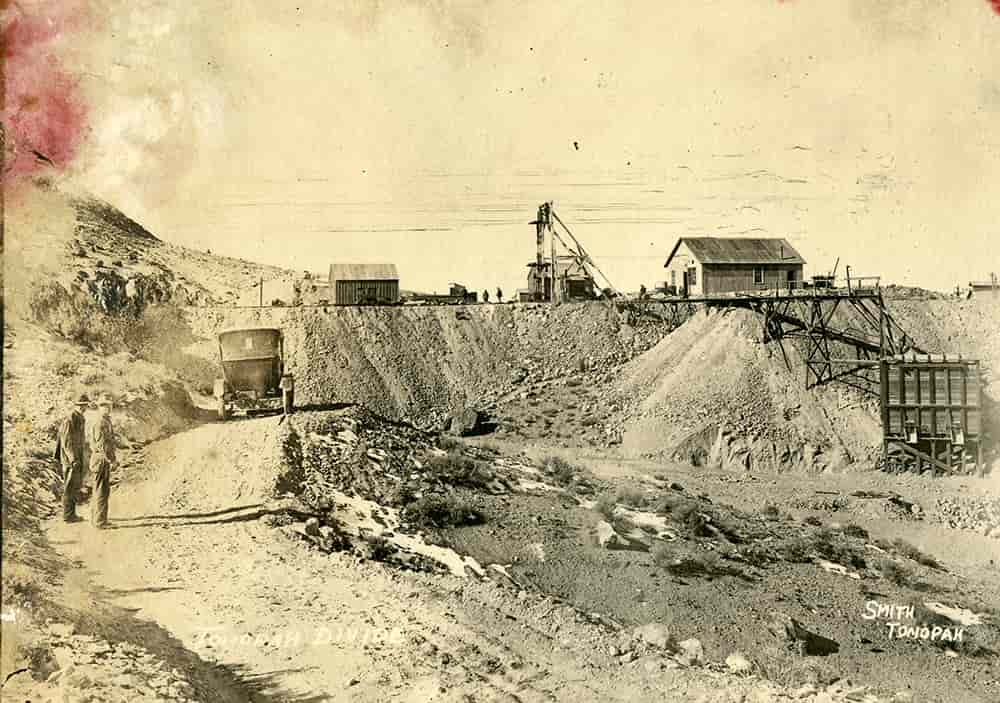

The Tonopah Divide Mine of which, George Wingfield was an owner; courtesy Special Collections Department, University of Nevada, Reno Libraries

Virginia City’s Comstock Lode fueled the economy of Nevada in the 1860s and ’70s—and, by extension, the mining stock markets of San Francisco. When mining operations began to close down around 1880, the entire state struggled.

Nevada would find its redemption in Tonopah, where Jim Butler, a ranch owner and amateur prospector, discovered Nevada’s next big strike in 1900. Legend has it that Butler came upon the rich outcroppings of ore while searching for one of his burros that had wandered away. He picked up a piece of rock to throw at the animal, but noticed that the rock appeared to be silver ore. When Butler filed mining claims in the area, he named one of the mines the ‘Burro.’

Jim Butler couldn’t afford to have the ore samples he collected assayed, so he partnered with Tasker L. Oddie—future U.S. Senator and Governor of Nevada—and local teacher Walter Gayhart. Still, the large losses at the end of the Comstock Lode hung over Nevada, and investors were hesitant to get mixed up in another mining venture. Development of the mines began slowly, but by 1901 the nearly $750,000 in gold and silver ore extracted from the mining district proved that Tonopah was not a flash in the pan.

Tonopah would in fact prove to be a steadier producer than Virginia City, with mining operations continuing for forty years with over $147 million in profits. Tonopah’s success led to a new push to prospect the region and new discoveries including nearby Goldfield, Bullfrog, Rawhide, and Manhattan. Tonopah became a center of financial and political power in the state, propelling the careers of men including George Wingfield, Patrick McCarran, and Key Pittman.

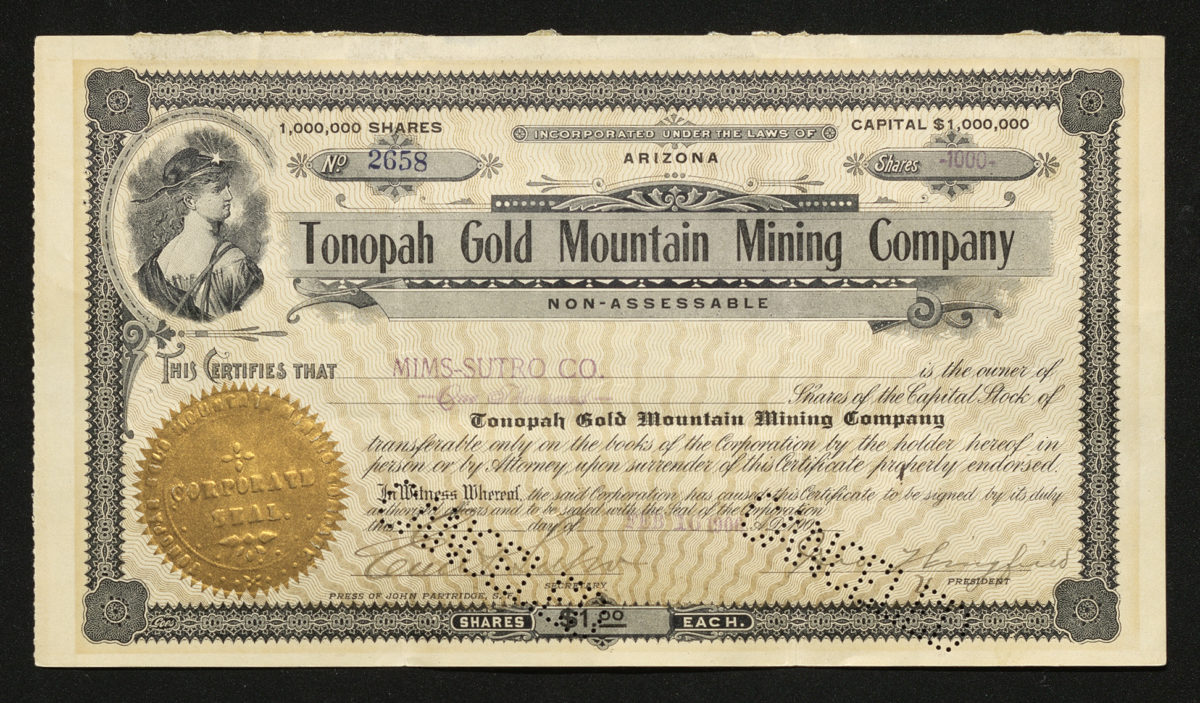

The Tonopah Gold Mountain Mining Company, a consolidation of mines that became the district’s largest producer, was formed in 1902 with Jim Butler initially serving as president. Two stock certificates from the Tonopah Gold Mountain Mining Company are included in the Schulich Historic Certificate Collection. The earlier one from 1904 has been signed by Key Pittman. Pittman served as a U.S. Senator from Nevada from 1913 to 1940, his tenure bookended with death. He had replaced Wingfield’s friend, Senator George Nixon, upon his death in office in 1913, and Pittman himself died in office. He famously earned reelection mere days before his death, giving rise to the myth that Nevada had elected a dead man and another that his body had been kept on ice in the Riverside Hotel in Reno so his party could maintain control after his election. During his time as a senator Pittman passed the Pittman Act in 1918, which fixed a minimum silver price subsidizing the silver mining industry. (Scroll down to continue reading about Tonopah and George Wingfield below)

The later stock certificate from 1906 is associated with two important figures in Nevada’s history: Georger Wingfield and Emil Sutro. Sutro, the son of Adolph Sutro of Sutro Tunnel fame, appears to have signed the certificate as secretary of the company, as well as being the bearer of the stock. George Wingfield has signed as president, along with his partner H.C. Brougher, who stepped in to control and reorganize the mining company in 1912 after it became mired in debt. At the time, newspapers proclaimed Wingfield to be the richest man in the state of Nevada, with an estimated fortune of $20 to $30 million built from the mines of Goldfield and Tonopah. Wingfield only became wealthier and more powerful as the newly organized company—the Tonopah Divide Mining Company—struck an especially rich lode of silver in 1917.

George Wingfield became an incredibly influential figure in Nevada business and politics; he has been called the ‘Owner and Operator of Nevada.’ He established banks throughout Nevada, invested in the development of many types of new business ventures, and built Reno’s Riverside Hotel which was designed by famed local architect Frederick DeLongchamps. Wingfield was not interested in becoming a politician—he felt he could do more to effect change in Nevada in his existing role—but he was actively involved in the world of politics. Wingfield used his influence to help a number of men get elected, including his friend and Nevada Governor Fred B. Balzar.

Wingfield’s legacy is mixed, with some people viewing him as the ‘Savior of Nevada,’ while others saw his power as tyrannical. Historian Elizabeth Raymond quoted a newspaper in 1931 which had vilified Wingfield:

When you speak of American democracy, leave Nevada out, for democracy is unknown there. One man controls the politics of the state, whether Democratic or Republican. One man controls the finances. One man controls the wills of the citizens and tells them what to think, what to vote. One man controls the legislature. One man controls the industries.

Whether benevolent or not, Wingfield’s monopoly was broken when he and his banks became embroiled in the Cole-Malley Embezzlement scandal of the 1920s. His banking empire collapsed, and he was forced into bankruptcy in 1935. Even so, Wingfield left a significant and permanent mark on the State of Nevada.

University of Nevada, Reno

University of Nevada, Reno