Tragedy Strikes at the Yellow Jacket Mine

The Yellow Jacket was one of the most successful mines of Nevada’s Comstock Lode, but it is primarily remembered for tragedy. Rumors swirled in the aftermath of the disaster, and construction on the Sutro Tunnel began as a result.

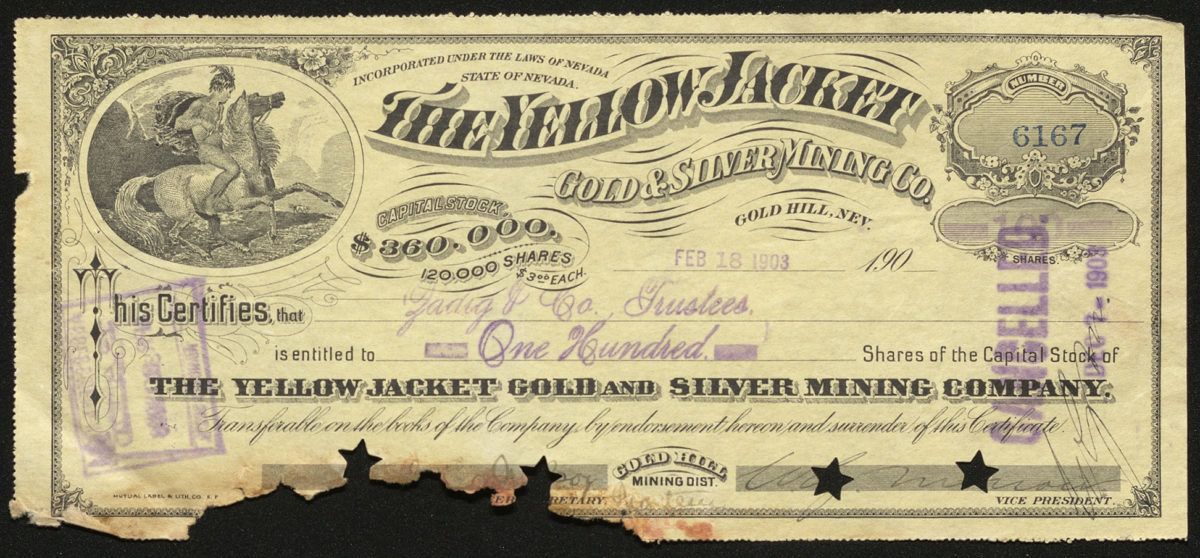

Header Image: Tunnel of the Yellow Jacket Mine filled with debris; courtesy Special Collections Department, University of Nevada, Reno Libraries [1].

“It crept through every tunnel shaft and incline and in a very short space of time scores of miners found themselves face to face with death.”

The Yellow Jacket Mining Disaster, 1869. Illustration originally from Dan De Quille’s The Big Bonanza; reproduced courtesy of Online Nevada Encyclopedia

The Yellow Jacket is one of the most famous mines on the Comstock Lode, sited just south of Virginia City in Gold Hill. The Yellow Jacket is one of many mines controlled by the powerful ‘Bank Crowd,’ a group of San Francisco bankers who controlled the Comstock around 1865–1875. William Sharon, the most prominent member of this group, took over ownership of the mine in 1867. It was one of the deepest mines on the Comstock, reaching 3,054 feet; it was also one of the best mines, producing $16.5 million in ore by 1889. The Yellow Jacket is not remembered for its successes, however; it is remembered as the site of one of the worst mining tragedies in Nevada history.

Mining was a hazardous profession; in a booming mining camp, hardly a day passed without death or injury occurring. Early on the morning of April 7, 1869, a fire started at the 800-foot level of the Yellow Jacket Mine and spread unnoticed as the day shift of miners were just arriving. The fire burned through the timbers supporting the mine and the ceiling collapsed, forcing noxious air throughout the mine’s tunnels and immediately suffocating several men. The Yellow Jacket’s shafts were connected to those of the nearby Kentuck and Crown Point mines—something that might normally provide a means of escape, but in this case endangered even more miners. A similar disaster would be repeated in Park City, Utah in 1902, when toxic gases released by a fire and explosion spread through the Daly-West Mine and killed unsuspecting miners in the adjoining Ontario Mine, with thirty-four souls lost. Stock certificates for these two mines are also included in the Schulich Western Collection.

Historian Ronald M. James chillingly describes the aftermath of the Yellow Jacket disaster: In the Crown Point, rescuers found nine of the dead clustered around an air pipe that they had severed in a desperate attempt to find a fresh air to stay alive. Elsewhere they found a miner with a death grip on the ladder, his head hanging backward. Here and there, strewn about the floors of the levels, were the scattered remains of the unfortunate morning shift. Those who explored the underground morgue found the mangled bodies of still others at the bottom of shafts. Having run through the dark passages in panic, those victims no doubt hope to find the cage but, misjudging their exact location, plunged to their deaths. (p. 86)

When firefighters realized they could not stop the blaze, they decided to seal off the shaft of the mine to try to starve it of oxygen—or at least control its spread. It was reported that the rock wall near the seal was hot to the touch as the fire continued to burn as many as three years later. It is believed that thirty-five miners were killed in the accident, though rescuers were not able to recover all of the bodies and thought more victims were incinerated in the fire. Some people believe that the mine is still haunted by the miners whose bodies were never recovered. The site of the mine has been featured on the Travel Channel show Ghost Adventures. (Scroll down to continue reading about the Yellow Jacket Mine Fire below)

After the disaster, rumors spread in San Francisco that the fire had been set intentionally by the mine’s owners as a way to manipulate stock prices. The mine’s owner William Sharon later repeated this accusation, this time leveling it against his political opponent in the race for U.S. Senate, John P. Jones, who had served as superintendent of the Crown Point Mine at the time of the disaster. The dirty tactic failed and Jones won the election. In 1874, Sharon threw his fortunes into campaigning again and won a seat as a Nevada Senator. He is remembered as one of Nevada’s worst politicians as he was largely absent from his post—even on matters affecting Nevada and silver prices.

A positive outcome of the disaster was that provided incentive to develop the Sutro Tunnel, a project to build a three-mile long horizontal tunnel that had been stalled by Sharon’s Bank Crowd for years. Adolf Sutro contended that the tunnel might have saved lives, though this is unlikely—the tunnel’s primary purpose was to drain water and extract ore from the mines in a more efficient manner. Still, the claim swayed public opinion and excavation of the tunnel began in 1869, the same year as the disaster.

University of Nevada, Reno

University of Nevada, Reno