William Walker’s Rise and Demise in South America

Colonial forces and tycoons were in competition for power and resources in South America in the 1800s; American William Walker crossed powerful men when he engaged in his military adventures throughout South America.

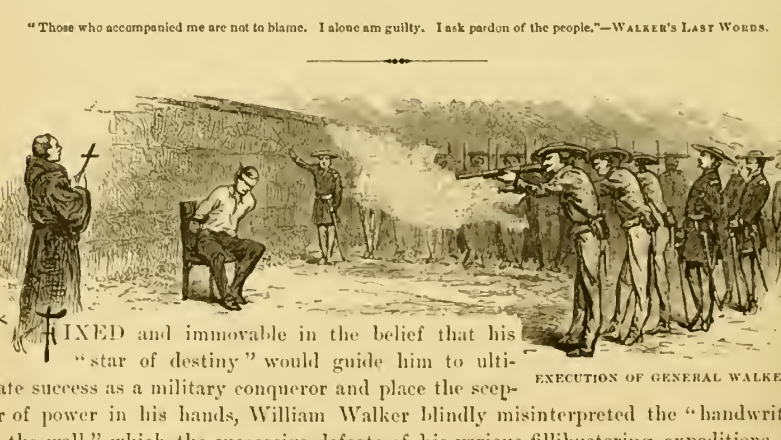

Header Image: The British did not take kindly to Walker’s incursions, and he was executed by firing squad September 12, 1860; courtesy of the Internet Archive [1].

“Vanderbilt was intent on destroying Walker as a matter of principle.”

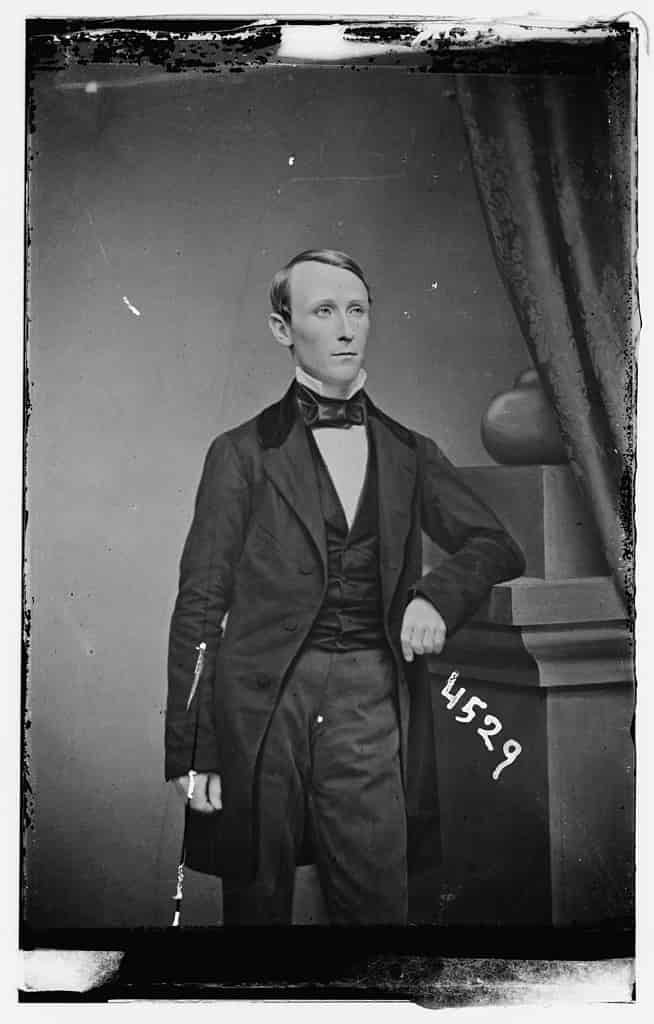

General William Walker, filibuster; courtesy Library of Congress

Prior to the American Civil War, William Walker was among the most famous filibusters in antebellum American history. In this period of Manifest Destiny, the term filibuster referred to someone who led unauthorized—and frequently illegal—military expeditions in foreign countries in order to establish colonies under their own personal rule. Leading up to the American Civil War, some filibusters were motivated to support the southern cause by acquiring territories that could in the future be annexed to the Union as slave states.

William Walker engaged in several attempts to establish and maintain control of self-declared republics in Mexico in the early 1850s. He went to San Francisco to sell bonds for the Republic of Sonora, but when he was prevented from returning, he instead seized La Paz as the “Republic of Lower California” in 1853. As president of this republic, Walker declared slavery legal. When this Republic quickly failed, Walker returned to U.S. with his tail between his legs but soon set sights on Nicaragua.

At the time, Nicaragua was in a key position in the trade route between New York and San Francisco, and Cornelius Vanderbilt owned the Accessory Transit Company that moved freight and passengers across the isthmus of Nicaragua. Political conflict in Nicaragua created an opportunity for Walker; leaders of the Liberal party recruited him to their cause in 1855 and hired him to bring American soldiers to support them. Walker quickly moved to take the country for himself. He commandeered Vanderbilt’s transit company, assumed the presidency of Nicaragua in 1856, and legalized slavery in the republic. Walker sought and received recognition as the legitimate ruler of Nicaragua from American President Franklin Peirce.

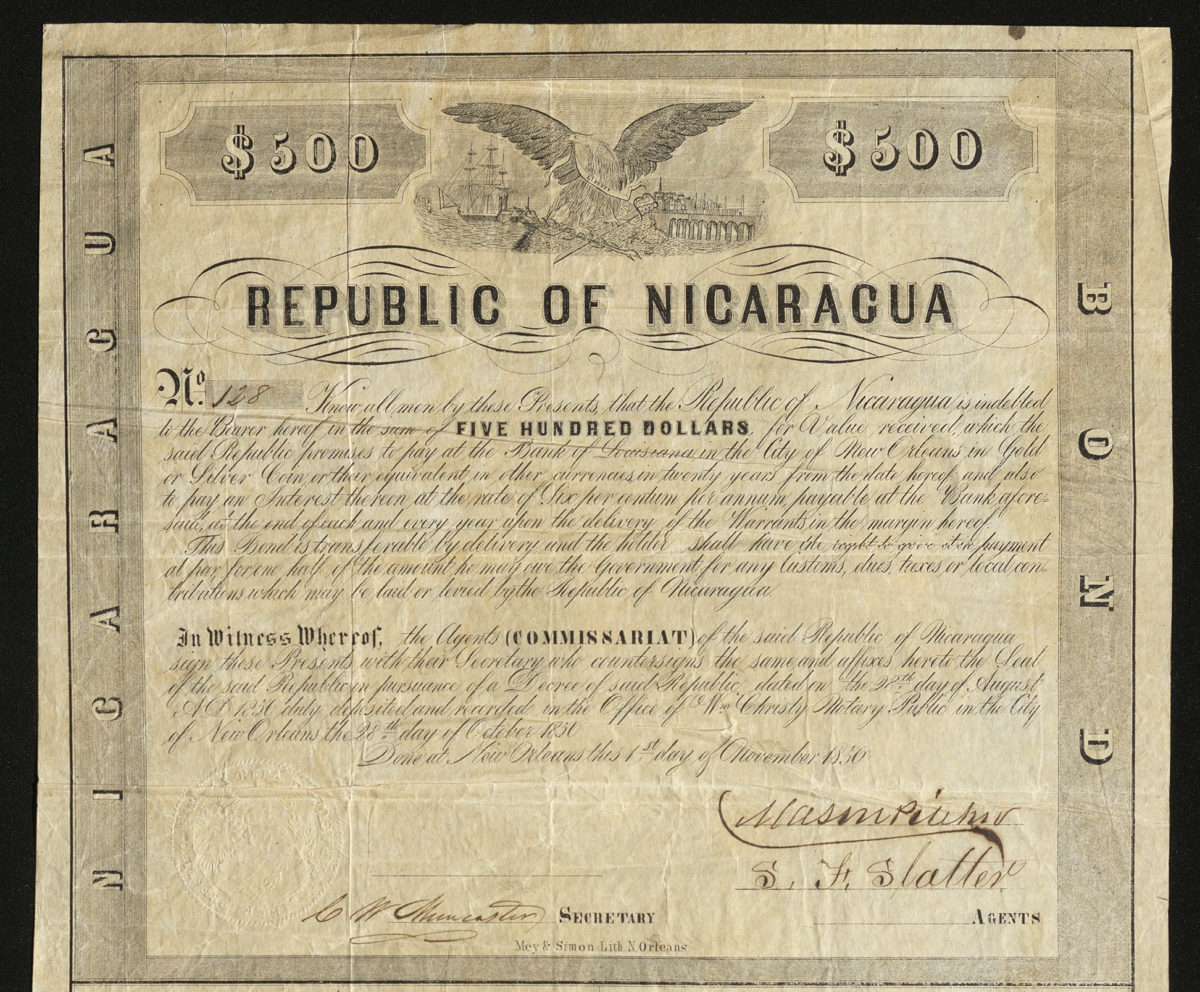

This is one of only two known copies of a $500 bond for the Republic of Nicaragua produced in 1856. While William Walker did not sign this document, it was produced at his behest. In the process of Walker’s connivances, he had made an enemy of Cornelius Vanderbilt, and the neighboring country of Costa Rica eyed his ambitions with caution. Walker knew to expect military retaliation, so he assigned Domingo de Goicuria the task of raising funds to defend his newly acquired republic. Goicuria soon realized that investors had little faith in Walker, and the Republic of Nicaragua and the bonds were slow to attract investors. He left two of his agents—who signed this bond—in New Orleans while he went to lobby Vanderbilt for support.

Goicuria was apparently unaware of Vanderbilt’s plans to depose and destroy Walker. Vanderbilt used his shipping company to transport weapons and gold to Costa Rican forces and sent agents to undermine Walker in Nicaragua, orchestrating Walker’s downfall. This bond has twenty interest warrants attached at the bottom which were never collected on, as they became worthless when Walker’s government lost legitimacy. Walker returned to the U.S., where he schemed to retake Nicaragua; when he did return to the area, he was captured by the British Navy. He was viewed as a threat to British holdings in the region, and executed by firing squad in Honduras at the age of thirty-six.

University of Nevada, Reno

University of Nevada, Reno